Елизавета Олеговна Безушко

Елизавета Безушко родилась и живёт в Николаеве. Сейчас она студентка 1-го курса Черноморского университета им. П. Могилы. Она пишет стихи и прозу, увлекается историей немого кино и японской культурой. Публикуется в журнале "Юность", литературно-общественном журнале «Голос Эпохи», интернет-журнале "Николаев Литературный". Участник ІІ Международного литературного конкурса "Верлибр", номинант премии "Писатель года - 2015"

You called me*

There was a sound of a small drum roll. First raindrops, which fall down so lubberly and swiftly, break into pieces against the fragile leaves, gracefully moving in time with the wind. Acacia creaked quietly and querelously and began to shake her branchy head. Drum roll became more rapid. It seemed that it was transformed into the kind of complicated drum rudiment just as if it heralded someone's appearance. Real and heavy rain was coming.

There was a sound of a small drum roll. First raindrops, which fall down so lubberly and swiftly, break into pieces against the fragile leaves, gracefully moving in time with the wind. Acacia creaked quietly and querelously and began to shake her branchy head. Drum roll became more rapid. It seemed that it was transformed into the kind of complicated drum rudiment just as if it heralded someone's appearance. Real and heavy rain was coming.

Oblong silver threads began to fall, tangling in the branches of poplars, making the bushes to shudder and sparrows frightenedly fly from one place to another.It seemed that it was only worth pulling for them and clouds, like balls of yarn, would have dissolved themselves. But this thought never entered anyone's mind, so the rain kept on going, piercing the sky and the earth with each other on the horizon line, drawn by someone.

The leaves continued to fall obediently, and puddles - to feel themselves like oceans, waiting for their discoverers. Multi-storey houses furtively looked into them out of the corners of their windows, as if in a mirror. Pigeons sat on the roofs, watching curiously umbrellas scurrying down the city streets.

- Rain again. The second time today, Deborah thought.

For the last half an hour she sat in an armchair cross-legged, listening attentively to the voice of a friend who came to her a thousand miles from the telephone receiver.She liked to chat with Virginia, although she often acted as a listener rather than as an interlocutor. And now she was terribly sorry that it was the only voice she deserved on this wet Sunday morning. She hugged her knees with one hand, and rested her head with the other. She was sad because it was raining and from the fact that tomorrow will come next Monday. She thought about the fact that with the advent of autumn the nights become longer, and the days off are shorter. Probably, therefore, any transition through the Rubicon, scheduled for Saturday or Sunday, is invariably postponed to the next weekend, and so until the end of time. Deborah remembered a stack of unread manuscripts left on the desktop on Friday. She shook her forelock, like a dissatisfied foal, and tried to throw it out of her mind. But she did not succeed, and she realized that she urgently needed to occupy herself with something.

She could no longer sleep, although she got up awfully early for the resurrection. In the living room for several minutes the phone did not stop. Someone persistently tried to get the tube still raised, and he succeeded. She hoped until the last time that at the other end of the line they were still going to contact her, but the phone definitely decided to take a vacant place of the alarm clock at the weekend. To get out on a rainy morning from a blanket so early for Deborah was akin to going off into space. Finally, she reluctantly left the cozy atmosphere of the blanket, throwing him off with a sharp movement.

The first to overcome the line of Karman, where the Earth's atmosphere ends and space begins, her legs, hanging helplessly from the bed. But then, putting a lot of effort, and her head still managed to tear herself away from such a soft and surprisingly comfortable pillow in the morning. And here the spacecraft "Deborah" found herself in a blinding with a bright morning light thermosphere. Grumbling something incomprehensible even to herself, she hurried barefoot on the cold floor to the phone.

How insulting was to make sure that someone made a mistake with the number! Something strange has been going on with the phone lately. Several times in the last two days people, who called her, were waiting to hear not her voice, and even she once phoned in the wrong place, where she was going to get through. Rather angry than frustrated, Deborah wandered back to bed, but did not get to sleep again. It's better to get up and make herself some coffee. Then she wanted to make her breakfast, but she caught the eye of a book, lying on the bedside table, whose last chapter had long been waiting for a suitable leisurely Sunday morning. After reading the book, she decided that it was necessary to do something useful. For example, to cook something. She likes to cook and always believed that it should be done by the call of inspiration, which for some reason left her recently. She remembered those "madeleines" she has tried with Virginia last week, and thought that somewhere she even has a linden tea. This will help her pass the day off, worthy of the French writer. She must call and find out the recipe.

Deborah phoned, and, immersed in an old armchair, chatted with a friend, where we found her. She was just listening carefully to Virginia's next story about how she forgot her glasses at home, poured coffee on someone, stumbled on the street "about nothing" and again forgot to buy food for her cat. When this story finally ended, Deborah, fearing that the next one would follow, hurried to tell her friend that she needed to walk the dog urgently, because Bushy looks at her with obvious discontent. This was only partly true. Deborah really had the dog Bush. He remotely resembled Jack Russell Terrier, his right eye adorned a chocolate spot, but his tail was bent, like a snail shell. But now he was fast asleep on the carpet beside her bed and would hardly be glad to offer a walk in this weather. However, this reason satisfied her friend and the telephone conversation was over. Deborah looked at the dog. She always wanted to wake him up when he slept so sweetly, but each time she overcomes this strange selfish desire.

Then she remembered that, after chatting with her friend for an hour, she did not recognize the recipe, and hastily dialed the number:

"Ginny, I forgot to find out your recipe for that cookie ... Madeleine, right? Proust liked it so much, "she rang out into the phone, before she could hear the girl's voice.

"Hello, Deborah.

A pause worthy of the theatrical scene hung in the air. It was the voice she least expected to hear. The voice that appealed from her past, was her past and now appealed to her. The first thing that occurred to her was to hang up. But she was recognized, so it would be rude. And, maybe, she is mistaken? She has to ask again. Swallowing the agitation, Deborah took in the lungs of air.

- Cary? She squeezed out softly, as if repeating someone's question.

- Are you surprised to hear me?

It is him. It's not too late to hang up. Or too late? It can't be him.

"But I called Virginia ..." she said, thinking aloud.

- No, you called me.

Deborah did not hear which of these words he stressed: "you" or "me," but his tone sounded somewhat self-assured and caught her. How can he so easily and quickly manage to anger her? This anger helped her to pull herself together.

- Well, I guess I mixed up some number, I was going to call my friend ...

"Yes, Virginia, I understand," he interrupted.

He always builds himself a clever man. And why did he decide that he could interrupt her?

"... and I was not going to bother you, Cary" she continued, in the voice of the interrupted, offended orator.

"Well, you did not bother me at all. Converserly, I am very glad that you have mixed up some number and got through to me.

The last phrase sounded much milder than all previous ones and again knocked Deborah off the strategy she had planned. And how can she answer this? She's not happy about that at all. But do not talk about it out loud. Not so she was brought up in childhood. And she did not come up with anything better than:

-Well, if I called you by chance, I find out ... How are you doing? She said in a puzzling voice and covered her eyes with her palm, hiding from her own stupid question.

At the other end, she heard a slight, declining awkwardness in her laughter.

- At me - is more likely not bad, and how are you?

Oh no. She was not going to discuss her business with him. This conversation needs to be finished as soon as possible.

-Me? Great, great. You know ... You know,it is so rainy this week, - she turned awkwardly.

"Yes, it does not look like autumn at all," he remarked in an ironically serious tone.

Now he laughs at her. It was high time to conclude this conversation.

"Listen ... Cary," she said his name after a moment's pause, as if she still could not believe that she was addressing him, "I really called you by accident." I would never ... - and she stopped.

-You would never call me? - he continued for her. - After three years for me this is not news.

"Besides, I need to urgently call Virginia," she continued, deliberately missing his words.

- Does someone's life depend on the cookie recipe?

- And how are you…? Oh yes. Don't you realize that I'm politely trying to end the conversation? "She suddenly burst out from his last caustic comment." If you had a little tact, you would help me finish the call, which I did not want at all. "

"How easy it is to get you out of yourself," Cary said. "I had enough tact not to notice that you don't want to continue this conversation." But this doesn't mean that I don't want this. I haven't heard you for a long time.

In his manner was to start any of his remarks sharply, as if trying to summon the interlocutor to a verbal duel, but to finish apologizing in a soft tone, smoothing out the impression from the words spoken before. And the impression of his last words, spoken in such a pleasant velvety voice, turned out to be so strong that they almost never offended him. Previously, it always worked with her, but now she strongly resisted.

"Now you heard me. I'm glad that something could please you. I'll just hang up, okay? Goodbye, Cary», - and Deborah was really determined to hang up, but she felt that their conversation was not over yet. Something else remained unclear, fuzzy, something needed clarification. And then she heard the words he said quickly:

"Debbie, wait, I still have not asked how Buffy is doing."

That's what it lacked: that he showed himself. So that behind the shell of the person whom she loved, appeared that one, a real man, whom she threw. With his shell, it was always harder for her to talk, because every second she convinces herself that in reality it is not a shell at all. But as soon as he showed himself, this difference could no longer be overlooked. Too terribly sharp, annoying and hopeless contrast. And when the real Carey once again became Carey, whom she loved, then for her in every movement, word, gesture, as if through a parchment, that one, the real one, shone through. Once she worked with rare old manuscripts in the publishing house, and therefore knew first-hand what parchment, though indispensable in restoration, is in itself a rather brittle and thin material. And so she was afraid that someday some sharp act or a sharp word would tear the parchment Cary, whom she loved so much, and instead of him will be a stranger with whom she could not be together. So it happened.

She always remembered why they broke up. Events, which did not mean anything to us, eventually turn into dusting facts in the vault of the memory. But the events that meant a lot to us, resist the corrosion of time. And if some details, unfortunately, leave our memory, feelings which we have experienced at that moment remain forever. You can say: "I do not remember what color was the sun diving in the sea at that moment, but I remember that feeling of happiness." Deborah always remembered that feeling and the reason why they broke up. And then, finally, he threw off those torn fragments of parchment oneself, behind which he hid at the beginning of their conversation, and now they can speak honestly.

"You know well that his name is Bushy. He is doing fine and, of course, not because of you.

"I knew you'd want to discuss this. I'm also interested in whether you didn't change your mind, he tried to hide his irritation behind his ironic intonation.

-About what?

"That this hairy flea-lump was more precious to you than your beloved."

"Stop it!" "Deborah's voice was raised, and then she continued in an artificially pathos tone." It wasn't about him. You're just not the person I loved anymore.

"I've heard all this before! This is all a good illusion, which you came up with and sincerely believed in it. I do not know what you've been thinking all the time and still seem to be, but I have not changed a bit! - The tranquility, for which he tried to hide, was shattered into thousands of fragments. He almost shouted the last words. Compared with his ironic, overly polite and gliding from one topic to another voice at the beginning of their conversation, this voice was angry, indignant, but alive. Deborah heard the annoyance with which the last phrase escaped from him, and it somehow touched her. In anger he always seemed to her particularly beautiful.

Cary, in turn, froze, frightened and surprised at his screaming, and decided to reduce the heat, adding:

- Well, maybe a little changed. I shaved off my beard.

At that end of the wire, he heard a sad laugh that had not been caught in time.

"Have you changed?" - he turned the conversation in her direction.

Deborah again lost her way with the planned strategy of conversation. She looked at Bushy awakened and after a pause replied:

-Yes. I learned to live without you - and was extremely surprised by this bold lie.

"It's beautiful, but not implausible," he said softly.

- It's none of your business. I made the decision, and I will not change it, "she snapped.

- Are you ready to bring your own happiness as a sacrifice of principle?

- What kind of happiness are we talking about? With the man who threw the living creature out of the house?

She often imagined this conversation. She thought out remarks for him, tried to pick up worthy arguments in her defense. He left her life, and his last steps turned into an ellipsis, which she tried to turn into a point. And now she had the opportunity to do it.

She told the truth. She was not used to changing the decisions she had already made. And when, on that spring evening, Deborah, feeling disappointed and devoted, said she did not want to see him again, she made a decision. She refused to believe that she was sorry for what she had said before. Although this thought often tormented her, in her heart of hearts she admitted to herself that she would do the same now. And this thought tormented her even more.

Then, three years ago, Deborah brought home a puppy. He lied under a tree beside a neighbour's house, his cold nose nuzzling his right paw. He was too thoroughbred to seem homeless, but too dirty and thin to sound like a domestic dog. As a child, she never had a dog, and in general her love for animals was reduced to the desire not to harm and help in case of theoretical urgency. But, seeing this puppy, Deborah suddenly felt that she should just take him home. Like there, under the tree, lied her best friend and waited for her to help him.

Crossed fingers, she waited, that nobody will respond to the announcement about the found puppy which she has submitted to newspapers and has hung in district. Bushy (as she decided to call the puppy) in gratitude for saving her from a sad fate was set up extremely friendly, but even this sincere friendliness irritated Carey. The very existence of a puppy in the house led him into hysterics. He decided to play the part of Deborah's conscience. Carey constantly reminded her that she had sheltered someone else's dog, and someone is now looking for this puppy. That he cannot love her as he loved his former masters. In general, the sooner she returns it, the better. The latter was his main cherished desire. Deborah knew that to some extent he was right, but did not even imagine the moment when she would have to give Bushy back. Fortunately, his former masters were not announced.

She tried to smooth the sharp corners, watching the puppy, which without malice was now and then ready to foul. Deborah didn't want to give Cary an opportunity to explode again and remind her of the treaty she was violating. But one day she didn't notice how Bushy made his way to the storeroom and gnawed at the men's shoes with childlike delight. Shoe from his favorite pair.

"I asked you to get rid of him as soon as possible!- he exclaimed.

It all ended, but when Deborah returned from work the next day, Bushy was not at home. "I did not throw it away, but took it to the orphanage," began Cary, explaining, holding the telephone receiver tightly to his face.

- It does not matter. You got rid of him, because he broke the harmony in the world of comfort in which you live. Where everything is done for you, the way you like and how it is convenient for you. In this world there is no one else but you alone. You threw the puppy out because he gnawed your shoes.He brought to you the slightest inconvenience, as you immediately deleted him from his life. And if we had a child and he would not let you sleep at night or pour tea on your trousers, would you throw it out too?

Deborah spoke hotly and quickly, as if she knew this monologue, and Cary could not put in a word. But there he interrupted her:

-Do not bend the stick, you can't compare the child and the puppy. You did not consult me when you decided to have an animal. For you, there has always been a place in my life, but I didn't give a consent about any living creatures. It seemed, that we have agreed with you not to have children and animals. But you still did as you wanted.

He doesn't hear her. He doesn't hear the main thing.

"All right", Deborah said again, "do you remember our last Christmas? All my life I celebrated it with my family, but you wanted us to spend Christmas together, remember? And I had to deny them, to say that I can't come to them. You have no idea how long they wait for this day, how they prepare for it and how happy they are to celebrate this holiday with me. But I deprived them of this happy day. When you wrote me a message almost on Christmas Eve, that the boss invited you to celebrate Christmas with his family, in his chic mansion, I thought you were joking. Then I thought that you were lying, and I called you in order to hear your voice and see for yourself. But you didn't answer. You wrote to me, Cary, you couldn't even call me! I still don't know with whom you spent this Christmas, and I will never ask you about it, but I spend it alone".

"You could have gone to your family," Cary said in a guilty voice.

"I was so ashamed", Deborah continued, more calmly, as if reflecting out loud, "so ashamed before them that I ... thought that you were someone else. I thought you were the very face in the crowd, so my heart was thinking. Or rather, it didn't think at all, it knew. And the doubts that crept into it just tore me apart. To go to my family ... After I refused them, saying that I will spend Christmas with you, how would it look? No, you just ruined that Christmas for me.

Then Deborah fell silent, expecting that after her words Cary's fiery monologuewill follow, his version. But all she heard from him after a long pause was:

-My boss really invited me. I could not refuse him, I'm very sorry.

Very sorry. All that he could squeeze out of himself. Everything he found necessary to say.

-You know, when we parted, and finally I could explain myself to my parents, my mother told me:" Why do you need a man who does not want to be with you on Christmas? " "But you did forgive me, gave me a second chance," Carey said in his former, charming, mildly persuasive voice. Apparently, he again decided to be friendly, - I did not think that this puppy can quarrel us.

- I was taught that people always need to give a second chance, but never give a third. This puppy became my friend, and you didn't understand this. You always didn't understand me very well. Maybe that's why I needed a friend.

Cary heaved a deep sigh. He never resisted the truth, and no matter how hard it was for him, he always accepted it. It was one of her favorite features in him. For some reason Deborah again felt sorry for him. A call from the past and a voice in the phone, which accuses him of all sins on a Sunday morning. No, you won't wish it even to the enemy. But he isn't her enemy at all. Deborah suddenly remembered the happiest day in her life. Cary remained silent and she asked: "Do you remember Belle-Ile?"

There was such sweet nostalgia in her voice that Cary didn't even think of looking for a catch in her question.

-Of course, it was a beautiful month.

- Really beautiful! - exclaimed Deborah and with pleasure immersed herself in memories - Before that I had never been to France. It looked like the sea was painted with watercolors. Such an amazing dark blue, flowing smoothly into soft turquoise, happens only in the waves of the Bay of Biscay. And seagulls! These graceful and unceremonious seagulls, watching every piece of baguette that you send into your mouth. Do you remember how we walked not far from the shore and came upon the pointer? And I asked: "Why is there no word" happiness "on the pointer? It must necessarily be somewhere around here.". And you answered ...

- And I answered: "Because it is everywhere."

- You do remember! Whispered Deborah.

-Of course I remember. Happiness really was there all over the place.

"Thank you," she said slowly. "Thank you for this month of happiness."

Deborah felt that it was urgent to change this trembling lyrical note to something more suitable for a telephone conversation.

- Are you living alone? - An inappropriate, but exciting question fell from her lips.

- Does that surprise you? His voice trailed off. Probably, he was stretched in an armchair or on a chair on which he was sitting. Apparently, his answer seemed to him the most abrupt, and he added:

"I'm never alone. My listeners and spectators are always with me".

"Yes," Deborah recalled, "you commented the last football match of our team. I switched channels and suddenly heard your voice. You'll see, soon you will be invited to some football show by an expert.

"Already invited!" "Cary said triumphantly," it always seemed to me that you knew me better than I did you. You are a mystery. But does the mystery lives by herself?

-I have Bushy.

This answer wasn't very satisfied with Cary, but Deborah interrupted him on the first interrogative sound:

- Do not ask questions. Don't repeat my mistakes.

-As you say,- Cary agreed.

Deborah suddenly felt that their conversation had come to an end. The cross-cutting theme of their conversation was exhausted, and on its background any general theme seemed too primitive and empty.

-I think it's really time for me. I didn't think that I would say this, but it was pleasant to talk with you, -this formula phrase had a deeper meaning told by Deborah.

- Me too, - and, for some reason suddenly agitated, Cary asked:

- But you will call again someday?

"N-no," Deborah was even more worried, and repeated more confidently: "No, I shall not. I even wouldn't have called this time.

"Then at least phone the wrong number sometimes," he joked. Deborah smiled.

- Farewell, Cary.

- Goodbye, Debbie.

Deborah hung up the phone. Debbie - so he called her before. Debbie. She got up from her chair, where she spent almost the whole morning, and covered her face with her hands, so that no one, even herself, could see what was written on it. Especially the eyes. They were too dangerously expressive. So awkward, so clumsily she ended their conversation. But what else could they say to each other? Suddenly the telephone rang again. Deborah froze. What does he wants? Maybe she doesn't have to pick up the phone. The temptation was too great. She approached the phone cautiously and put her fingers around the receiver.

- Yes?

- Deb, I forgot, you wanted a cookie recipe from me. Is there a pen or pencil next to you? Write ...

Virginia brought her back to her own apartment, on a rainy Sunday morning. He won't call her. As she won't call him.

This conversation put an end which she had so much dreamed of and was so afraid. But for some reason it was a soothing, soft point. She could not explain even to herself why . Probably, because earlier it seemed to her that the point is the inevitable end of everything. The place where life is interrupted, the end of the world. But the impatient, cheerful and vibrant voice of Virginia, who was already dictating something to her on the phone, made Deborah think for the first time that she had enough strength to start a new paragraph. This point will always be with her, but completing one sentence, the point invariably marks the beginning of a new one.

"Wait, wait, I'll take a pencil," Deborah said, and, not hearing the answer, put down the receiver.

Having scratched Bushy's ear, she went to the next room to find at least one sharpened pencil in her desk drawer.

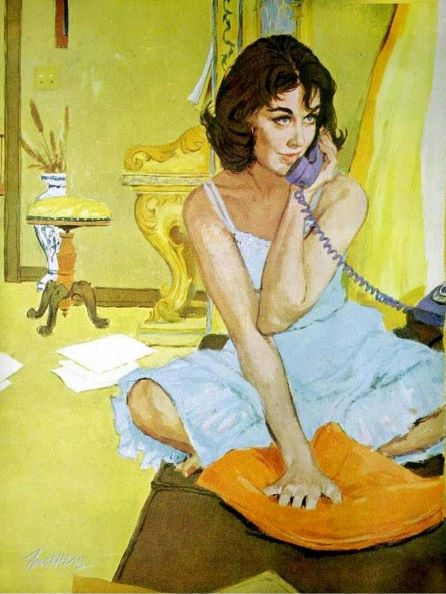

* illustration by Lynn Buckham

Ты позвонила мне*

Последние полчаса она провела сидя в кресле, поджав ноги и внимательно слушая голос подруги, который доносился к ней через тысячу миль из телефонной трубки. Она любила болтать с Виржинией, хотя чаще выступала в роли слушателя, чем собеседника. И всё же ей было ужасно жаль, что это был единственный голос, который она заслужила в это воскресное промокшее утро. Одной рукой она обхватила колени, а другой опёрла голову. Ей было грустно от того, что шёл дождь, а ещё от того, что завтра наступит очередной понедельник.

Спать она больше не могла, хотя встала ужасно рано для воскресения. В гостиной несколько минут не умолкал телефон. Кто-то упорно добивался, чтобы трубку всё-таки подняли, и ему это удалось. Она до последнего надеялась, что на том конце провода всё-таки отчаются с нею связаться, однако телефон определённо решил занять пустующее в выходные место будильника. Выбраться дождливым утром из одеяла так рано для Деборы было сродни выходу в открытый космос.

До чего же было обидно убедиться в том, что кто-то ошибся номером! С телефоном в последнее время творилось что-то странное. Уже несколько раз за последние два дня ей звонили люди, ожидавшие услышать не её голос, и даже она один раз попала не туда, куда собиралась дозвониться. Скорее разозлившаяся, чем расстроенная, Дебора побрела обратно в кровать, но вновь уснуть не получилось.

Тут она вспомнила, что, проболтав с подругой час, так и не узнала рецепт, и второпях набрала номер:

- Джинни, я ведь забыла у тебя узнать рецепт того печенья… «Мадлен», да? Которое Прусту так нравилось,- протараторила она в трубку, не успев услышать голоса подруги.

- Здравствуй, Дебора.

Пауза, достойная театральной сцены, повисла в воздухе. Это был голос, который она менее всего ожидала услышать. Голос, который взывал из её прошлого, был её прошлым и теперь обращался к ней. Первым, что пришло ей в голову, было положить трубку. Но её узнали, значит, это было бы грубо. А, может быть, она ошибается? Нужно переспросить. Проглотив волнение, Дебора набрала в лёгкие воздуха.

-Кэри? – тихо выдавила она из себя, словно повторяя чей-то вопрос.

- Удивлена слышать меня?

Это он. Ещё не поздно положить трубку. Или поздно? Этого не может быть.

- Но я ведь звонила Вирджинии…- сказала она, думая вслух.

- Нет, ты позвонила мне.

Дебора не расслышала, на каком из этих слов он поставил ударение: «ты» или «мне», но его интонация показалась ей несколько самоуверенной и зацепила её. Как ему так легко и быстро удаётся её злить? Эта злость помогла ей взять себя в руки.

- Что ж, наверное, я перепутала какую-то цифру, я собиралась позвонить своей подруге…

- Да, Вирджинии, я так и понял, - прервал он её.

Вечно он строит из себя умника. И с чего это он решил, что может перебивать её?

- …и вовсе не собиралась побеспокоить тебя, Кэрри, - продолжила она голосом прерванного обиженного оратора.

- Что ты, ты совсем меня не побеспокоила. Наоборот, я очень рад, что ты перепутала какую-то цифру и дозвонилась мне.

Последняя фраза звучала значительно мягче всех предыдущих и вновь сбила Дебору с намеченной ею стратегии. И как ей ответить на это? Она ведь этому совсем не рада. Но не стоит говорить об этом вслух. Не так её воспитывали в детстве. И она не придумала ничего лучше, чем:

-Раз уж я тебе случайно позвонила, узнаю... Как у тебя дела? – сказала она псевдобеззаботным голосом и прикрыла ладонью глаза, прячась от собственного глупого вопроса.

На том конце послышался лёгкий, рассекречивающий её неловкость смешок.

- У меня - скорее неплохо, а как у тебя?

О нет. Она совсем не собиралась обсуждать с ним свои дела. Этот разговор нужно поскорее закончить.

- У меня? У меня – отлично. Знаешь…Знаешь, на этой неделе на редкость дождливая погода, - неуклюже вывернулась она.

- Да, совсем не похоже на осень, - заметил он иронично серьёзным тоном.

Теперь он смеётся над ней. Этот разговор уже давно пора было завершить.

- Послушай…Кэри, - она произнесла его имя после секундной паузы, словно всё ещё не могла поверить, что обращается к нему, - я действительно позвонила тебе случайно. Я ведь никогда бы не…- и она осеклась.

-Никогда не позвонила бы мне? – продолжил он за неё, - Спустя три года для меня это не новость.

- К тому же, мне нужно срочно позвонить Вирджинии, - продолжила она, намеренно пропустив его слова мимо ушей.

- Чья-то жизнь зависит от рецепта печенья?

- А как ты…? Ах, да. Разве ты не понимаешь, что я вежливо пытаюсь закончить разговор?- вдруг взорвалась она от его последнего колкого замечания, - Будь у тебя хоть немного такта, ты бы помог мне закончить звонок, которого я совсем не хотела.

- Как легко тебя вывести из себя, - заметил Кэри, - У меня хватило такта не заметить того, что ты не хочешь продолжать этот разговор. Но это не значит, что этого не хочу я. Я давно тебя не слышал.

В его манере было начинать любую свою реплику резко, словно пытаясь вызвать собеседника на словесную дуэль, а заканчивать извиняющееся мягким тоном, заглаживая впечатление от сказанных до этого слов. И впечатление от его последних слов, сказанных таким приятным бархатным голосом, оказывалось настолько сильным, что на него почти никогда не обижались. Раньше это всегда срабатывало и с ней, но теперь она решительно сопротивлялась.

- Теперь ты меня услышал. Рада, что чем-то смогла тебе угодить. Я просто положу трубку, хорошо? Прощай, Кэри, - и Дебора была действительно настроена положить трубку, но она чувствовала, что их разговор ещё не окончен. Что-то ещё осталось невыясненным, нечётким, что-то требовало разъяснения. И тут она услышала быстро произнесённые им слова:

- Дебби, постой, я ведь ещё не спросил, как поживает Буффи.

Вот чего не хватало: чтобы он проявил себя. Чтобы за оболочкой человека, которого она любила, показался тот, настоящий человек, которого она бросила. С его оболочкой ей всегда было тяжелее разговаривать, потому что каждую секунду она убеждала себя, что на самом деле это вовсе не оболочка. Но стоило ему проявить настоящего себя, как эту разницу больше невозможно было не замечать.

Она всегда помнила, из-за чего они расстались. События, ничего для нас не значившие, со временем превращаются в пылящиеся в хранилище памяти факты. Но события, которые значили для нас много, сопротивляются коррозии времени. И если какие-то детали и, к сожалению, покидают нашу память, в ней навсегда остаются чувства, которые мы испытывали в тот или иной момент. Вы можете сказать: «Я уже не помню, какого цвета было нырявшее в море заходящее солнце в ту минуту, но помню то ощущение счастья». Дебора всегда помнила то чувство и причину, по которой они расстались. И вот, наконец, он сбросил с себя те рваные обрывки пергаментного себя, за которыми от прятался в начале их разговора, и теперь они могут разговаривать честно.

- Ты ведь прекрасно знаешь, что его зовут Буши. Он поживает прекрасно и, конечно же, не благодаря тебе.

- Я знал, что тебе захочется это обсудить. Мне же интересно вот что: не переменила ли ты своего мнения, - он пытался скрыть за ироничной интонацией свою раздражённость.

-Какого мнения?

- Что этот волосатый блохастый комок оказался для тебя дороже любимого человека.

- Прекрати! – повысила голос Дебора, и затем продолжила искусственно-пафосным тоном, - Дело было вовсе не в нём. Просто ты уже не тот, кого я любила.

- Я всё это уже слышал! Это всё удачная иллюзия, которую ты придумала и сама же в неё искренне поверила. Не знаю, что тебе всё время мерещилось и мерещится до сих пор, но я не изменился ни на йоту! – деланное спокойствие, за которым он пытался укрыться, разлетелось на тысячи осколков. Последние слова он уже почти кричал. По сравнению с его ироничным, излишне вежливым и скользящим от одной темы к другой голосу в начале их разговора, этот голос был разозлившийся, негодующий, но живой. Дебора услышала досаду, с какой из него вырвалась последняя фраза, и это почему-то тронуло её. В гневе он всегда казался ей особенно прекрасен.

Кэри в свою очередь замер, испугавшись и удивившись своему крику, и решил снизить накал, добавив:

- Ну, разве что чуть-чуть изменился. Я сбрил бороду.

На том конце провода послышался не успевший вовремя быть пойманным печальный смех.

- А ты изменилась? – повернул он разговор в её сторону.

Дебора вновь сбилась с намеченной стратегии разговора. Она посмотрела на проснувшегося Буши и после паузы ответила:

-Да. Я научилась жить без тебя – и необычайно удивилась своей смелой лжи.

-Красиво, но неправдоподобно, - мягко заметил он.

- Это не твоё дело. Я приняла решение, и я его не изменю, - резко ответила она.

- Ты готова принести своё счастье в жертву принципиальности?

- О каком счастье идёт речь? С человеком, который выбросил из дома живое существо?

Она не раз представляла себе этот разговор. Придумывала за него реплики, пыталась подобрать достойные аргументы в свою защиту. Он ушёл из её жизни, и его последние шаги превратились в многоточие, которое она силилась превратить в точку. И вот ей представилась возможность это сделать.

Она сказала правду. Она не привыкла менять уже принятые решения. И когда в тот весенний вечер Дебора, почувствовав себя разочарованной и преданной, сказала, что не хочет его больше никогда видеть, она приняла решение. Она отказывалась верить в то, что сожалеет о сказанном сгоряча. Хотя эта мысль нередко мучила её, в глубине души она признавалась себе, что и сейчас поступила бы так же. И эта мысль мучила её ещё больше.

Тогда, три года назад, Дебора принесла домой щенка. Он лежал под деревом у соседнего дома, уткнувшись холодным носом в правую лапу. Он был слишком породистым, чтобы казаться бездомным, но слишком грязным и худым, чтобы походить на домашнего пса. В детстве у неё никогда не было собаки, и в целом её любовь к животным сводилась к желанию не навредить и помочь в случае теоретической острой необходимости. Но, увидев этого щенка, Дебора вдруг почувствовала, что просто должна забрать его домой. Словно там, под деревом, лежал её лучший друг и ждал, что она поможет ему.

Скрестив пальцы, она ждала, что никто не откликнется на объявление о найденном щенке, которое она подала в газеты и развесила в округе. Буши (так она решила назвать щенка) в благодарность за спасение от печальной участи был настроен чрезвычайно дружелюбно, но даже эта искренняя дружелюбность раздражала Кэри. Само существование щенка в доме приводило его в истерику. Он решил играть роль совести Деборы. Кэри постоянно напоминал ей, что она приютила чужого пса, и кто-то сейчас ищет этого щенка. Что он не сможет полюбить её так, как любил своих прежних хозяев. В общем, чем скорее она вернёт его, тем лучше. Последнее было его главным заветным желанием. Дебора знала, что в какой-то степени он прав, но даже не представляла себе момент, когда ей придётся отдать Буши обратно. К счастью, его прежние хозяева не объявлялись.

Она старалась сглаживать острые углы, следя за щенком, который без злого умысла то и дело готов был напакостить. Деборе не хотелось дать Кэри повод вновь взорваться и напомнить ей о договоре, который она нарушает. Но однажды она не заметила, как Буши пробрался в кладовую и с детским восторгом сгрыз мужской туфель. Туфель из его любимой пары.

- Я просил тебя избавиться от него как можно скорее! – воскликнул он.

Этим все и кончилось, но когда на следующий день Дебора вернулась с работы, Буши дома не оказалось.

-Я его не выбросил, а отнёс в приют,- начал было объяснять Кэри, крепче прижав телефонную трубку к лицу.

- Это не важно. Ты избавился от него, потому что он нарушал гармонию в мире комфорта, в котором ты живёшь. Где всё делается для тебя, так, как тебе нравится и как тебе удобно. В этом мире нет ни для кого места, кроме тебя одного. Ты выбросил щенка, потому что он испортил тебе туфель. Стоило ему причинить тебе малейшее неудобство, как ты тут же вычеркнул его из своей жизни. А если бы у нас был ребёнок и он не давал бы тебе спать по ночам или разлил бы чай тебе на брюки, ты тоже выбросил бы его на улицу?

Дебора говорила разгорячено и быстро, словно знала этот монолог на зубок, и Кэри не мог вставить и слова. Но тут он прервал её:

-Не перегибай палку, нельзя сравнивать ребёнка и щенка. Ты не посоветовалась со мной, когда решила завести животное. Для тебя в моей жизни всегда было место, но насчёт всякой живности я согласия не давал. Мы ведь, кажется, договорились с тобой не заводить детей и животных. Но ты всё равно сделала так, как захотела.

Он не слышит её. Он не слышит главного.

- Хорошо, - вновь начала Дебора, - помнишь наше последнее Рождество? Всю свою жизнь я праздновала его со своей семьёй, но ты хотел, чтобы мы провели Рождество вдвоём, помнишь? И мне пришлось отказать им, сказать, что я не могу приехать к ним. Ты не представляешь, как долго они ждут этот день, как готовятся к нему и как счастливы, праздновать этот праздник со мной. Но я лишила их этого счастливого дня. Когда ты написал мне сообщение почти что в канун Рождества, что босс пригласил тебя отпраздновать Рождество с его семьей, в его шикарном особняке, я подумала, что ты шутишь. Потом я подумала, что ты врёшь, и позвонила тебе, чтобы услышать твой голос и убедиться в этом. Но ты не взял трубку. Ты ведь написал мне, Кэри, ты даже позвонить мне не смог! Я до сих пор не знаю, с кем ты провёл это Рождество, и никогда тебя об этом не спрошу, но я провела его одна.

- Ты могла поехать к своей семье, - виноватым голосом произнёс Кэри.

- Мне было так стыдно, - уже более спокойно, словно размышляя вслух, продолжила Дебора, - так стыдно перед ними, что я…обозналась. Я думала, что ты-то самое лицо в толпе, так думало моё сердце. Вернее, оно и вовсе не думало, оно знало. И сомнения, которые закрались в него, просто разрывали меня. Поехать к своей семье… После того, как я отказала им, сказав что проведу Рождество с тобой, как бы это выглядело? Нет, то Рождество ты мне точно испортил.

Тут Дебора затихла, ожидая, что после её слов, последует пламенный монолог Кэри, его версия. Но всё, что она услышала от него после долгой паузы, было:

- Меня действительно пригласил босс. Я не мог ему отказать, мне очень жаль.

Очень жаль. Всё, что он смог выдавить из себя. Всё, что нашёл нужным сказать.

- Знаешь, когда мы расстались, и я наконец-то смогла объясниться с родителями, мама сказала мне: «Зачем тебе мужчина, который не хочет быть с тобой в Рождество?».

- Но ты ведь меня простила, дала мне второй шанс, - сказал Кэри своим прежним обворожительным, мягко убеждающим голосом. Видимо, он снова решил быть дружелюбным, - Я и не думал, что этот щенок способен нас рассорить.

- Меня учили, что людям всегда нужно давать второй шанс, но никогда не давать третий. Этот щенок стал моим другом, а ты не понял этого. Ты всегда не очень хорошо меня понимал. Возможно, поэтому мне понадобился друг.

Кэри тяжело вздохнул в трубку. Он никогда не сопротивлялся правде, и как бы ему ни было тяжело, всегда принимал её. Это была одна из её любимых черт в нём. Деборе почему-то снова стало его жаль. Звонок из прошлого и голос в телефонной трубке, который обвиняет его во всех грехах воскресным утром. Нет, такого не пожелаешь даже злейшему врагу. А ведь он ей совсем не враг. Дебора вдруг вспомнила самый счастливый день в своей жизни. Кэри продолжал молчать и она спросила:

- Ты помнишь Бель-Иль?

В её голосе звучала такая сладкая ностальгия, что Кэри даже не пришло в голову искать в её вопросе подвох.

-Конечно, это был прекрасный месяц.

- Действительно прекрасный! – воскликнула Дебора и с удовольствием погрузилась в воспоминания, - До этого я никогда не была во Франции. Море было словно нарисовано акварельными красками. Такой умопомрачительный тёмно-синий, плавно перетекающий в мягкий бирюзовый, бывает только в волнах Бискайского залива. А чайки! Эти грациозные и бесцеремонные чайки, наблюдающие за каждым кусочком багета, который ты отправляешь в рот. А помнишь, как мы гуляли недалеко от берега и набрели на указатель? И я спросила: «Почему на указателе нет слова «счастье»? Оно непременно должно быть где-то здесь». И ты ответил…

- И я ответил: «Потому что оно здесь повсюду».

- Ты помнишь! – прошептала Дебора.

-Конечно, я помню. Счастье и вправду было там повсюду.

-Спасибо тебе, - медленно произнесла она, - спасибо тебе за этот месяц счастья.

Дебора почувствовала, что нужно срочно сменить эту дрожащую лирическую ноту на что-то более подходящее для телефонного разговора.

- Ты живёшь один? – неуместный, но волнующий её вопрос сорвался с её уст.

- Тебя это удивляет? – его голос отдалился.

Наверное, он потянулся в кресле или на стуле, на котором сидел. Видимо, его ответный вопрос показался ему самому резким, и он добавил:

- Я никогда не бываю один. Со мной всегда мои слушатели и зрители.

-Да,- вспомнила Дебора, - ты комментировал последний футбольный матч нашей сборной. Я переключала каналы и вдруг услышала твой голос. Увидишь, скоро тебя пригласят на какую-нибудь футбольную передачу экспертом.

- Уже пригласили! – торжествующе заметил Кэри, - мне всегда казалось, что ты знаешь меня лучше, чем я тебя. Ты - загадка. А загадка живёт сама по себе?

-У меня есть Буши.

Этот ответ не очень удовлетворил Кэри, но Дебора прервала его на первом вопросительном звуке:

-Не задавай вопросы. Не повторяй моих ошибок.

- Как скажешь, - согласился Кэри.

Дебора вдруг почувствовала, что их разговор подошёл к концу. Сквозная тема их разговора была исчерпана, а на её фоне любая общая тема казалась слишком примитивной и пустой.

-Я думаю, мне действительно пора. Не думала, что скажу это, но мне было приятно с тобой пообщаться, - произнесённая Деборой эта шаблонная фраза имела более глубокий смысл.

- Мне тоже, - и, почему-то вдруг заволновавшись, Кэри спросил: - Но ты ведь позвонишь ещё когда-нибудь?

- Н-нет, - ещё больше заволновалась Дебора и повторила более уверенно: - Нет, не позвоню. Я и сейчас не позвонила бы.

- Тогда хотя бы ошибайся номером иногда,- пошутил он.

Дебора улыбнулась:

- Прощай, Кэри.

-Прощай, Дэбби.

Дебора положила трубку. Дэбби – так он её называл раньше. Дэбби. Она встала из кресла, в котором провела почти целое утро, и закрыла лицо руками, чтобы никто, даже она сама, не увидел, что на нём сейчас написано. Особенно глаза. Они у неё были слишком опасно выразительны.

Так неловко, так неумело она завершила их разговор. Но что ещё они могли сказать друг другу?

Вдруг тишину комнаты вновь пронзил телефонный звонок. Дебора замерла. Чего он хочет? Может, не нужно брать трубку. Соблазн был слишком велик. Она осторожно подошла к телефону и обхватила пальцами трубку.

- Да?

- Деб, я ведь совсем забыла, ты у меня хотела рецепт печенья узнать. Есть рядом ручка или карандаш? Пиши…

Вирджиния вернула её в собственную квартиру, в дождливое утро воскресенья. Он не позвонит ей. Как и она ему. Этот разговор поставил точку, о которой она так мечтала и которой так боялась. Но почему-то это была успокаивающая, мягкая точка. Почему она и сама не могла объяснить. Наверное, потому что раньше ей казалось, что точка - это неминуемый конец всего. Место, где жизнь прерывается, край света. Но нетерпеливый, бодрый и полный жизни голос Вирджинии, который уже диктовал что-то ей в трубку, заставил Дебору впервые задуматься о том, что у неё хватит сил начать новый абзац. Эта точка всегда будет с ней, но завершая одно предложение, точка неизменно знаменует начало нового.

-Подожди, подожди, я возьму карандаш, - сказала Дебора, и, не услышав ответа, отложила трубку.

Потрепав по дороге Буши за ухо, она отправилась в соседнюю комнату, чтобы найти в ящике своего письменного стола хоть один заточенный карандаш.

*Иллюстрация - Линн Бакхэм,"Девушка, разговаривающая по телефону"